When Moroccan Soldiers Joined the Vietnamese People in the First Indochina War

Special Contribution: Anna Mahjar-Barducci

Modern Tokyo Times

We cannot fully understand Vietnam’s history without explaining what happened in the country during WWII. In September 1940, Vietnam was occupied by Japan, which was part of the Tripartite Pact. Japan managed to seize control of Vietnam after France – the colonial power in the region – was subdued by Nazi Germany in 1940, with the establishment of German occupation zones and the collaborationist Vichy regime. The Japanese takeover of Vietnam began when France signed an agreement with Japan allowing the deployment of 6,000 Japanese troops in northern Vietnam. Within a few weeks, the Japanese military seized control of the entire country. When Japan surrendered to the Allies in 1945 after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it withdrew from Vietnam, which found itself with no government at all.

The End of WWII And Vietnam’s Independence

In the resulting political vacuum, the charismatic Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh, who during WWII took charge of the Viet Minh to fight against the Japanese occupiers and the Vichy-Nazi collaborators, declared Vietnam’s independence on September 2, 1945. During the historic declaration at Ba Ming Square, Ho Chi Minh cited the U.S. Declaration of Independence: “All men are created equal. They are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable Rights; among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” He then stressed: “We are convinced that the Allies, which at the Teheran and San Francisco Conferences upheld the principle of equality among the nations, cannot fail to recognize the right of the Vietnamese people to independence.”

The United States, however, did not provide Vietnam with the support it ostensibly should have, even though it had maintained contacts with Viet Minh forces during the war. Rather, the U.S. offered its support to Britain and China (which at the time was led by the anti-communist Kuomintang government), which restored the French colonial rule in Vietnam. By 1946, Saigon (today Ho Chi Minh City) fell under French colonial control. Unphased, the Viet Minh bravely retaliated, and by December 1946, the two sides were openly at war.

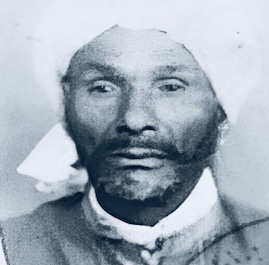

MY GRANDFATHER ABOVE – AHMED MAHJAR

Drafting Moroccan Soldiers to the Indochina War

In order to bolster its new war effort in Vietnam, which would last more than seven years and which later became known as the First Indochina War, France began to draft soldiers from its colonies in Africa.

Among those drafted from France’s colonies in Africa was my grandfather, Ahmed Mahjar. Ahmed was a native Moroccan, and he had considered himself an anti-fascist since Moroccan soldiers had fought for the liberation of France during WWII. In 1943, my grandfather had been sent along with thousands of other Moroccans to fight in Corsica against Italian Fascist occupation forces. He had also been sent to various regions in France to confront Nazi troops. In the spring of 1952, he was then drafted to Indochina.

Choosing the Right Side of History

When he arrived in Vietnam, he was overwhelmed by the country’s beauty, culture, cuisine, and hospitality. He saw that the Viet Minh forces that confronted him on the battlefield were fighting for freedom, and he realized that this scenario was different from when he was in France fighting against the oppression of the racist Fascist and Nazi ideologies – this time, he felt like he was fighting on the side of the oppressor.

At the time, those Moroccan soldiers fighting in Indochina were similarly aspiring for independence for their own country. The Moroccan independence movement was steadily growing during these years, and it aimed to establish an independent monarchy under the leadership of Sultan Mohammed V. However, in 1953, France would force the Sultan and his family into exile, first in Corsica and then in Madagascar.

For my Moroccan grandfather, it was impossible to continue fighting for a colonial power that was oppressing the Vietnamese people and their independence movement the same way that it was oppressing his own people’s hopes and aspirations. Together with hundreds of other Moroccan soldiers (according to some sources, the total number was 250), Ahmed Mahjar decided to choose the right side of history: He rebelled against the colonialist power and joined the Vietnamese people in their struggle for freedom and independence.

Ultimately, the Indochina War became very unpopular among the French public, and in May 1954, France was finally defeated by Viet Minh forces at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu. What followed was the declaration of the 1954 Geneva Accords, which split Vietnam along the 17th Parallel into the socialist North, led by President Ho Chi Minh, and the West-aligned South. This arrangement was meant to be temporary, with a promise that elections would take place in 1956 to reunite the country, but the U.S. eventually backed South Vietnam’s decision to cancel the elections. Vietnam would only be officially reunited “from Cao Lang to Cau Mau” on July 2, 1976, after the end of the long and bloody Second Indochina War (commonly known as the Vietnam War) and after North Vietnamese forces seized final control of Saigon.

“The Morocco Gate” and “The Vietnam Gate”

I don’t know exactly when and how my grandfather, who passed away many years ago, returned to Morocco, which achieved its independence from France in 1956 (two years after the end of the Indochina War), with Sultan Mohammad V regaining control of the kingdom. Many Moroccan soldiers indeed did not succeed to return to Morocco after the end of the war and were only repatriated in 1972. Many of these Moroccans ended up marrying Vietnamese women, and their descendants today live in Morocco and share both cultures.

Between 1956 and 1960, the Moroccan soldiers who had defected from the French army and remained in Vietnam built the Morocco Gate in Hanoi’s Ba Vi district. The gate still serves as a monument to honor those courageous Moroccan fighters who contributed to the liberation of a fellow country from the yoke of colonialism. More recently, in the Moroccan province of Kenitra, where my grandfather resided alongside several families of Vietnamese origin, the Vietnam Gate was dedicated; this gate symbolizes the two countries’ shared values and common past of struggle and sacrifice, as well as the cooperation among free and equal nations.

The President of the Morocco-Vietnam association, Dr. El Mostafa El Ktiri, who is Morocco’s High Commissioner for Former Resistance Fighters and Former Members of the Liberation Army, stated that the “historical memory” shared by the two countries was created by the mobilization of Moroccan soldiers who joined the Vietnam liberation movement and who believed in the value of freedom. He also recalled the role of anti-colonialist Moroccan leader Abdelkrim El Khattabi (1882-1963), whose guerilla tactics against France and Spain (the two colonialist powers in Morocco) are said to have had a significant influence on President Ho Chi Minh, and whose words about self-sacrifice for the sake of independence inspired many Moroccans to defect from the French Army.

Ideals Move Nations

The story of my grandfather and his fellow Moroccan soldiers teaches us that it is ideals that move nations. These young fighters did what was necessary and chose to stand against colonial rule and fight for the ideal of a free world in which sovereign countries can cooperate in equal partnership and participate in global development. They were ready to live and die for this.

Today, as I try to honor the memory of my grandfather, I cannot but think that the Vietnamese people, who managed to overcome terrible damage and suffering, continue to serve as a source of inspiration with their resilience, taking their well-deserved place in the world.

Anna Mahjar-Barducci is a Moroccan-Italian researcher and author.

amahjarbarducci@yahoo.com – Anna Mahjar-Barducci

PHOTOS:

1st and 3rd (Source: Moroccan Royal Archives)

4th image: Gate of Morocco in Hanoi, Vietnam