Japanese Art and Nature

Lee Jay Walker

Modern Tokyo Times

Matsubayashi Keigetsu (1876–1963) stands as a serene guardian of tradition, a calm and contemplative presence against the restless tides of modernity. In his hands, Nanga—the literati style born of Chinese poetic philosophy—becomes more than an artistic lineage; it becomes a breathing cosmos. His brush moves with the cadence of old verse, shaping mountains like meditations, mists like whispered sutras, and distant moons like memories half-remembered from another world. Each stroke carries an inner stillness, a decorative harmony that reveals the quiet radiance of a mind steeped in culture and reflection.

During the Meiji and Taishō eras, when Japan’s artistic compass swung eagerly toward Western winds, many painters embraced oil, realism, and imported ideals. Keigetsu instead walked the ink-worn path of the ancients, following the subtle currents that had long flowed between China and Japan. His devotion to classical aesthetics was neither defiance nor nostalgia—it was continuity. Through him, the venerable spirit of the literati endured: unhurried, introspective, and eternally attuned to the dialogue between mountain, river, void, and brush.

The Japanese artist Nishimura Shigenaga (1697-1756) pursued his calling with a quiet, unwavering conviction. Long before his name found its place within the floating world of ukiyo-e, he tended a modest bookshop in the environs of Kanda—today’s bustling heart of Tokyo. Amidst shelves of printed wisdom and the gentle rustle of turning pages, he educated his own eye, teaching himself the subtleties of line, form, and narrative. It was in these quiet hours, after the day’s commerce had faded, that his artistic spirit quietly matured.

As time unfurled, the guiding lights of Okumura Masanobu and Nishikawa Sukenobu began to illuminate his path. Their influence entered his work with the grace of a tide—steady, shaping, and refining. Once Shigenaga firmly established himself within the ukiyo-e tradition, these refinements blossomed: his figures gained composure and poise, his compositions acquired elegance, and his technique carried the confident imprint of a man who had forged himself through study, perseverance, and an enduring devotion to art.

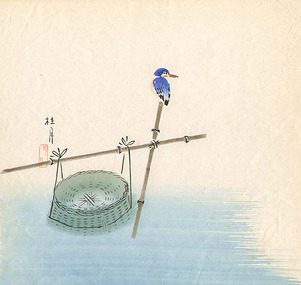

The Japanese artist Nishimura Goun (1877–1938) entered the world in the early Meiji Period—a time when Japan’s foundations trembled beneath the weight of modernization, and when old and new clashed like shifting seasons. Yet in Goun’s work, especially in these three exquisite depictions of birds, one senses a soul that listened more closely to the quiet echoes of the past than to the clamor of the modern age.

Born in Kyoto—the timeless heart of Japanese culture—Goun absorbed the refined spirit that had flowed from Nara to the ancient capital for over a millennium. This cultural inheritance breathes through his art with luminous clarity. Each feather, each delicate gesture of wing and beak, is rendered with an elegance that speaks of classical aesthetics, temple calm, and the disciplined grace of traditional brushwork. These birds are not merely creatures of nature; they are emissaries of an older Japan, poised between serenity and symbolism.

In Goun’s hands, the present bows gently to the past, and the past stirs once more with quiet, contemplative life.

Modern Tokyo News is part of the Modern Tokyo Times group

http://moderntokyotimes.com Modern Tokyo Times – International News and Japan News

http://sawakoart.com – Sawako Utsumi’s website and Modern Tokyo Times artist

https://moderntokyonews.com Modern Tokyo News – Tokyo News and International News

PLEASE JOIN ON TWITTER

https://twitter.com/MTT_News Modern Tokyo Times

PLEASE JOIN ON FACEBOOK