Japanese Novelist and Ryūnosuke Akutagawa: A Troubled Soul

Lee Jay Walker

Modern Tokyo Times

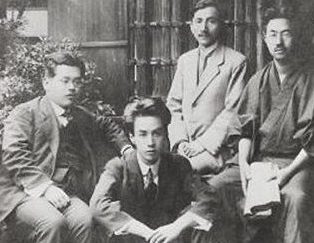

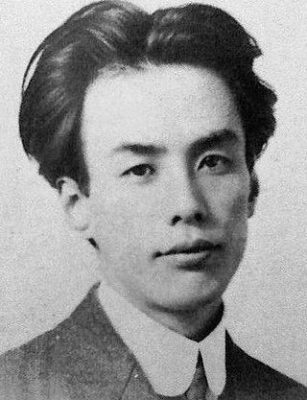

The Japanese novelist Ryūnosuke Akutagawa (1892–1927) first drew breath in the restless outskirts of Tokyo—a city caught between the twilight of tradition and the blaze of modernity. Though born amid the Meiji Restoration (1868–1912), his spirit and his art belonged unmistakably to the fragile and feverish Taishō era (1912–1926)—a brief, flickering age of intellect and uncertainty.

Soon after his birth, darkness descended upon his family. His mother, tormented by the shadows of madness, slipped beyond reach. Thus, the infant Akutagawa was taken in by his maternal uncle, whose home became both his refuge and his crucible.

From the earliest years of his awakening, the young Akutagawa was captivated by the written word. He devoured the luminous prose of Natsume Sōseki and the austere classics of ancient China, finding in their pages both solace and purpose. In time, the pen became his destiny—a blade to dissect human frailty and a mirror to reflect the anguish of a mind too brilliant, and too fragile, for its age.

He wrote (The Life of a Stupid Man), “What is the life of a human being—a drop of dew, a flash of lightning? This is so sad, so sad.”

During the turbulent years of early twentieth-century Japan, writers became the conscience of a nation in flux. Some, like Takiji Kobayashi (1903–1933)—who would meet a cruel death under torture for his Communist convictions—channeled the rage and despair of the oppressed. Their pens bled with the cries of the downtrodden, capturing the clash between the powerful and the powerless.

Others, however, turned inward. Among them stood Akutagawa, whose art delved not into the struggles of the masses but into the labyrinths of the human soul. The Taishō Period thus became a crucible of ideas—a brief yet incandescent age where countless voices, philosophies, and dreams converged upon the page.

For Akutagawa, Sōseki was more than a literary idol; he was a guiding light. It was Sōseki who first recognized the young writer’s genius, publishing his early tales “Rashōmon” and “Hana” (The Nose), and praising the latter in 1916. That single gesture—Sōseki’s public approval—ignited the flame of Akutagawa’s career, ensuring that the literary world would watch his every move with breathless anticipation.

By 1918, Akutagawa’s life appeared luminous with promise. He married Fumi Tsukamoto, a union that seemed to anchor him amid the shifting tides of fame. At the same time, his creative powers soared: he produced a wealth of haiku and poetic works, among them “Gesaku Zanmai” (A Life Devoted to Gesaku, 1917) and “Hōkyōnin no Shi” (The Death of a Christian, 1918, also known as The Martyr). These pieces revealed a mind fascinated by faith, irony, and the tragic beauty of human contradiction—hallmarks of a genius whose brilliance would soon flicker into torment.

Ominosuly, he wrote (Life of a Stupid Man), “As he thought about his life, he felt both tears and mockery welling up inside him. All that lay before him was madness or suicide. He walked down the darkening street alone, determined now to wait for the destiny that would come to annihilate him.”

In 1921, while on assignment for the Osaka Mainichi Shinbun, Akutagawa journeyed to China, a land steeped in both antiquity and unrest. There, amid the dust of foreign streets and the feverish pulse of empire, his frail body betrayed him. Illness shadowed his every step; the experience, though brief—merely four months—etched a lingering fragility upon his soul.

When he returned to Japan, it was as though he had crossed not only nations but thresholds of the mind. From then until his tragic death by suicide in 1927—after one earlier, desperate attempt—Akutagawa lived in the uneasy twilight between creation and collapse. His final years were a tormenting symphony: ceaseless writing, deteriorating health, and the creeping terror that madness, the same that had claimed his mother, was tightening its grip upon him. Hallucinations haunted his nights, and by day he wrestled with the crushing anxiety of life’s formlessness—that “vague uneasiness” which he himself named as the seed of his destruction.

Akutagawa wrote, “Life is more hellish than hell itself.”

And yet, even in death, his voice refused silence. From the ink of his anguish bloomed a legacy that would ripple far beyond his era. His stories—fragmentary, brilliant, and cruelly human—ignited the imaginations of writers, filmmakers, and artists across generations. The name Ryūnosuke Akutagawa became immortal: the tragic genius whose life burned swiftly, yet whose light still flickers through the corridors of modern culture.

In his haunting final work, Kappa, Akutagawa laid bare the fractured mirrors of his own mind. The tale—centered on the mythical Kappa, those mischievous water-spirits of Japanese folklore—became far more than a fable. Beneath its strange, satirical surface seethed the torments of a man unraveling, and the uneasy conscience of an age.

Through the eyes of a psychiatric patient who tumbles into the bizarre underworld of the Kappa, Akutagawa conjured a landscape both grotesque and revelatory—a distorted reflection of Taishō Japan, with all its brilliance, decay, and spiritual disarray.

Yet within this phantasmagoria lies a profound duality: the patient and the author are one and the same, each staring into the abyss of their own despair. Accordingly, the descent into the Kappa’s realm mirrors Akutagawa’s own passage into madness, his search for meaning amid the crumbling borders of sanity.

Thus, Kappa stands not merely as allegory but as confession—a final, fevered whisper from a mind too lucid to bear its own clarity, poised on the brink of oblivion.

Modern Tokyo News is part of the Modern Tokyo Times group

http://moderntokyotimes.com Modern Tokyo Times – International News and Japan News

http://sawakoart.com – Sawako Utsumi and Modern Tokyo Times artist

https://moderntokyonews.com Modern Tokyo News – Tokyo News and International News

PLEASE JOIN ON TWITTER

https://twitter.com/MTT_News Modern Tokyo Times

PLEASE JOIN ON FACEBOOK

https://www.facebook.com/moderntokyotimes