Japanese Art: Buddhism and Dramatic Skylines

Lee Jay Walker

Modern Tokyo Times

Kanzan Shimomura (1873–1930) stands as one of Wakayama’s most celebrated artistic sons. Born amid the sweeping transformations of the Meiji era and passing in the early years of the Showa period, his life spanned a time of profound change in Japan. Between these defining epochs lay the more tranquil and liberal Taisho period (1912–1926), often seen as a gentle interlude in an otherwise tumultuous age.

Yet, in the artwork above, Shimomura reaches beyond the present of his time. Rather than fully embracing modernity, he forges a delicate bridge to the past—evoking a sense of reverence for tradition, and imbuing his work with the quiet spirit of classical Japan.

Hanabusa Itchō (1652–1724) was a fiercely independent spirit in the world of Edo-period art—a painter, poet, and provocateur whose life was marked by both brilliance and defiance. His uncompromising nature eventually led to imprisonment and a long exile. Yet, even during those years of isolation, his creative flame did not dim. When he finally returned, tempered perhaps with political caution, he continued to subvert artistic norms with a quiet, sharpened boldness.

Itchō began his journey within the refined discipline of the Kano school, where he studied under Kano Yasunobu, absorbing its formal techniques and courtly elegance. But while these teachings shaped his foundation, it was his poetic voice that first brought him wider acclaim—a voice rich in wit, humanity, and irreverent insight.

The Met Museum says, “Daruma (the Japanese abbreviated pronunciation of the Sanskrit Bodhidharma) was among the most common subjects for Zen monk-painters. Born in India in the 6th century A.D., Daruma is recognized as the first patriarch of Chan (Japanese: Zen) Buddhism in China.”

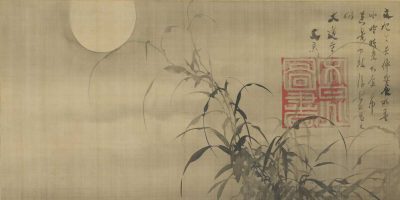

The artwork above is by Tani Bunchō (1763–1840), a master of the Edo Period whose brush moved with the spirit of a scholar and the soul of a poet. As a leading figure of the Bunjinga (literati painting) tradition, Bunchō stood among kindred spirits such as Kameda Bōsai, Hanabusa Itchō, Ike no Taiga, Watanabe Kazan, and Tomioka Tessai—artists who saw painting not merely as craft, but as a philosophical and cultural pursuit.

Though Japan was largely closed to the outside world during the Edo era, Bunchō’s gaze turned toward the distant yet revered land of the Middle Kingdom—China, the wellspring of classical thought, refined brushwork, and timeless aesthetics. Through ink, line, and verse, he paid homage to Chinese ideals, immersing himself in its artistic heritage with a sense of awe and quiet longing.

In Bunchō’s world, mountains were more than landscapes—they were meditations. Pines were not merely trees, but emblems of endurance. And behind every stroke lay a dialogue with the past, carried across seas and centuries.

Modern Tokyo News is part of the Modern Tokyo Times group

http://moderntokyotimes.com Modern Tokyo Times – International News and Japan News

http://sawakoart.com – Sawako Utsumi and her website – Modern Tokyo Times artist

https://moderntokyonews.com Modern Tokyo News – Tokyo News and International News

PLEASE JOIN ON TWITTER

https://twitter.com/MTT_News Modern Tokyo Times

PLEASE JOIN ON FACEBOOK