Art of Japan During the Edo Period: Tani Buncho and Culture of China

Lee Jay Walker

Modern Tokyo Times

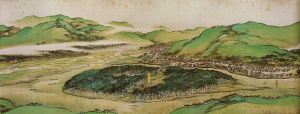

In the history books it is stated that Japan in the Edo period was cut off from the outside world but the old ways persisted and certain daimyo maintained aspects of past trade depending on geography. Therefore, culture, ideas, philosophy, art, religion, the written language of kanji, gardens, architecture, and other notable areas that had been influenced by China, were still revered by many Japanese artists.

Tani Buncho was born in 1763 and died in 1840. Sadly, the policies of Edo infringed on his art work because he was forbidden to go to China. This was based on the policy called sakoku (locked country). Sakoku forbade the free movement of individuals to foreign countries and on foreigners entering Japan. However, while this was strictly implemented with regards to individuals the real terminology should be kaikin (maritime prohibitions) because trade continued with others in Ryuku, in Ainu areas, Nagasaki, and a couple more places – therefore, Japan wasn’t fully isolated.

Also, while the clampdown on Christianity was a reality and converts would be killed without haste, it is abundantly clear that the Edo period did not infringe on the teaching of other non-Japanese indigenous faiths and philosophies that came to Japan via China and Korea. Given this, Chinese ideas ran through the veins of Japanese society. This can be seen by the ruling elites adopting Edo Neo-Confucianism therefore greater stratification took place. The samurai also built many Confucian academies therefore while the movement called Kokugaku would emerge with greater power and influence, this applies to focusing on Japanese culture, history, the Shinto faith and ancient literature, the ruling way would remain.

Therefore, the world of Buncho was one of deep admiration for Chinese classics and high culture despite all the political constraints in relation to free travel and other important areas. Not surprisingly, Buncho and other artists were constrained by this reality therefore different thought patterns in China and Japan would further split with regards to contemporary ideas emanating from China. Given this reality, Buncho visited Nagasaki where trade was allowed in special areas between outsiders and Japanese traders.

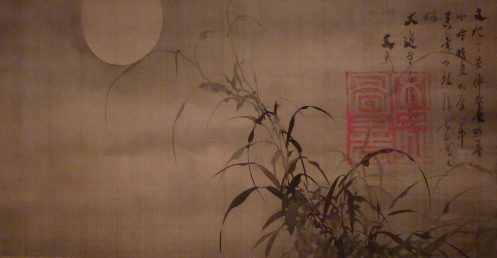

Buncho, just like Kameda Bosai, Hanabusa Itcho, Ike no Taiga, Watanabe Kazan, Tomioka Tessai, and many others, belonged to the Bunjinga school of thought. This school of thought flourished in the late Edo period and highlights the power of traditional Chinese culture in Japan despite the ongoing isolation of this nation. The Bunjinga, the literati according to their mode of thinking, all had one binding feature and this applies to their deep admiration of traditional Chinese culture. This enabled their individuality to be linked together within the ideas and art work of Bunjinga concepts.

On the British Museum website it states: “The Japanese Bunjinga school of literati ‘scholar-amateur’ artists flourished in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It is also known as Nanga (‘Southern painting’). The school was based on the literati movement that developed in China over a long period of time as a reaction against the formal academic painting of the Northern Song dynasty (960-1126). Rather than technical proficiency, literati artists cultivated a lack of affectation in an attempt to tune in to the rhythms of nature. In Japan, this was only partially understood: many Japanese bunjin were simply trying to escape the restrictions of the academic Kanō and Tosa schools while imitating Chinese culture. At first, the only models available were woodblock-printed manuals such as the Kaishien gaden (‘Mustard Seed Garden’) and a few imported Chinese paintings. Some Chinese monks of the ōbaku Zen sect taught painting in Nagasaki. Unlike their Chinese counterparts, the Japanese bunjin were not necessarily carefree artists and scholars from wealthy, bureaucratic backgrounds, and many had to sell their work to make a living.”

Buncho focused heavily on his love of traditional Chinese culture but this talented individual also studied other art forms including Tosa, Western-style and the world of ukiyo-e. Therefore, he was an individual who searched the many art-forms that were available to him, irrespective of the limitations imposed by Edo rulers.

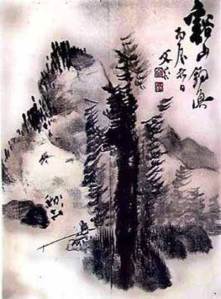

The Saru Gallery comments about Buncho by stating that: “He first studied Kanō painting at a young age with Katō Bunrei, then the Nanga style under Watanabe Gentai, Kitayama Kangan and Kushiro Unsen. During his travels he met the patron Kimura Kenkadō, who became a life-long friend. Through him he met many artists from the Kansai area, including Uragami Gyokudō and Yamamoto Baiitsu. He studied many other styles of painting then current in Japan, including Chinese and Western style. His work is widely eclectic, and brought him many friends, fans and pupils. In the end he was mainly known as a Nanga artist, who brought the literati style style from Kyoto and Osaka to the capital.”

Buncho moved to Nagasaki for many years in order to study Chinese art and European art and in many ways he is a “microcosm” of issues that have pulled at Japan for many centuries. This applies to the power of Japanese culture, Chinese culture, and Western culture, and how best to utilize or to focus on one main area. However, for individuals like Buncho he yearned for knowledge and greater wisdom. Therefore, he focused on all the positives from each culture in order to express himself through art but of course the old world of China influenced him greatly.

The legacy of Buncho is multiple and this applies to his books he wrote about art and theory, his art work, his thinking and how he overcame the many restrictions imposed on him and society because of the policies of Edo. Also, it is intriguing to note that despite the isolation of Japan during the Edo period it is clear that outside thought patterns were still powerful in this nation. Therefore, “windows” like Nagasaki enabled Buncho to learn more about new ideas while the old world of China survived based on many cultural realities.

http://jyuluck-do.com/profile_tani_buncho.html

http://moderntokyotimes.com Modern Tokyo Times – International News and Japan News

http://sawandjay.com Modern Tokyo Times – Fashion

https://moderntokyonews.com Modern Tokyo News – Tokyo News and International News

http://global-security-news.com Global Security News – Geopolitics and Terrorism

PLEASE JOIN ON TWITTER

https://twitter.com/MTT_News Modern Tokyo Times

PLEASE JOIN ON FACEBOOK

https://www.facebook.com/moderntokyotimes

Some Japanese art and cultural article by Modern Tokyo Times are republished in order to inform our growing international readership about the unique reality of Japan.