Art of Japan and the “Annual Rites and Ceremonies” to the suffering of the boy Emperor

Lee Jay Walker

Modern Tokyo Times

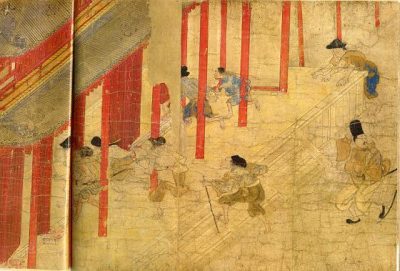

The artist Tokiwa Mitsunaga was highly acclaimed in twelfth-century Japan. This notably applies to his “Annual Rites and Ceremonies” dated in 1173. Hence, people can get an insight into the various ceremonies that lit up the compound of the palace.

Mitsunaga lived during a very dramatic period for Japan. This relates to important historical events that took place between 1156 and 1185, involving the clans of Taira and Minamoto. Therefore, the flows of power concentration and intrigues filled the world of Mitsunaga during his most productive period.

In a past article, I comment, “One can only imagine how Mitsunaga viewed the power dynamics that were shaping Japan. After all, the world of the Heian Period (794-1185), in simplistic terms, is famous for the influence of the Middle Kingdom (China), Buddhism, and Taoism. Equally important, tensions inside the Middle Kingdom enabled Japanese culture to become more independent (kokufu bunka) and this, in turn, boosted art, literature, poetry, and other areas of Japanese high culture.”

The ultimate demise of the Taira led to the tragic death of the young boy Emperor Antoku (1178-1185). This child – born into the clan intrigues of Taira and Minamoto -would ultimately drown in the deepwater of the Shimonoseki Straits. Thus, the dramatic ending of the Battle of Dan-no-ura witnessed Antoku’s grandmother dropping the boy Emperor into the unforgiving sea. Thereby, the demise of Taira was truly tragic and based on the ultimate sacrifice.

Indeed, it is reported that Mitsunaga perished in the same year that Minamoto emerged victorious – and the same year that the child Emperor Antoku lost his life at the hands of his kin, who sought to protect him from vengeance. Thus, the Minamoto power dynamics of 1185-1333 (officially came into existence in 1192) witnessed the Kamakura Period.

I stress in a past article, “Sadly, the original “Annual Rites and Ceremonies” and “Imperial Procession” were lost to fire. However, as the Phoenix rises, then the same applies to the art of Mitsunaga because esteemed artists would copy from what was handed down. Hence, attributes and a clouded history connect people in modern times with the twelfth-century artist Mitsunaga.”

Overall, it is not known how Mitsunaga viewed the ending of the Heian Period in 1185. Yet, it is fair to suggest that the growing rise of the samurai will have alarmed him. Thus, just like his world was ending – and that of Emperor Antoku that had not begun – feudalism and the bakufu (tent government) would alter the power dynamics of Japan based on the samurai (warrior caste). Therefore, Mitsunaga provides a glimpse of the old world before it was swept away by the Minamoto clan.

PLEASE DONATE TO HELP MODERN TOKYO TIMES

Modern Tokyo News is part of the Modern Tokyo Times group

DONATIONS to SUPPORT MODERN TOKYO TIMES – please pay PayPal and DONATE to sawakoart@gmail.com

http://moderntokyotimes.com Modern Tokyo Times – International News and Japan News

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/moderntokyotimes/ Modern Tokyo Times is now on PINTEREST

http://sawakoart.com – Sawako Utsumi personal website and Modern Tokyo Times artist

https://moderntokyonews.com Modern Tokyo News – Tokyo News and International News

PLEASE JOIN ON TWITTER

https://twitter.com/MTT_News Modern Tokyo Times

PLEASE JOIN ON FACEBOOK