Dutch Court Case Reignites Europe’s Focus on ISIS Children

by Abigail R. Esman

Special to IPT News

Investigative Project on Terrorism

He is a handsome boy, about 9 or 10 years old, with large, pale green eyes and dark hair. He speaks softly, conversing with a Western journalist.

“We will kill you,” he says, as casually as he might say, “I am going for a walk.” “We will slaughter you.”

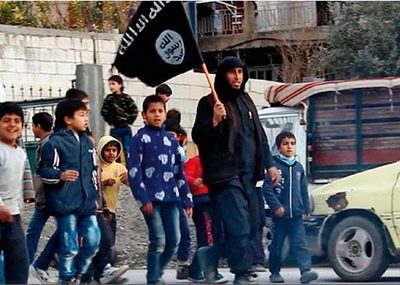

He is one of the children of ISIS, raised in the Caliphate to become a jihadist and to fight for the Islamic State. His words should come as no surprise; children were born in ISIS territory – and continue to be born in the Kurdish camps where many remain imprisoned – for one purpose: to be better, stronger, more devoted jihadists than the generation before them.

ISIS leaders made no secret of the fact that women in the Caliphate had one key role to fill – motherhood. They were to have children, and many of them, so that those children could become part of the next generation of warriors.

Now a battle in the Dutch courts has caused chaos and fear regarding the future of these children and their mothers. On Nov. 11, judges in The Hague ordered the government to travel to the Syrian camps and repatriate the 56 Dutch children currently being held there. Some of them have never lived anywhere else, and have had no schooling other than their training for jihad.

The government immediately appealed, citing the dangers of sending emissaries to the region; within days, appeals court judges issued an emergency ruling in their favor, calling the issue a political, not a judicial one. Meantime, the Parliament continues to debate the issue.

The situation is also being watched closely by the rest of Europe, for which either the first ruling or the appeal could become a working model. What’s more, given Europe’s open borders, each of these children poses a potential threat, not only to the Netherlands, but to the entire European continent. What happens in each EU country matters to the rest.

At the same time, the situation similarly poses countless moral and humanitarian questions that may also affect international security. Can, or should, a child be forcibly removed from his mother? How likely is it that his anger and resentment over this separation make him all the more antagonistic to the country that has, in essence, kidnapped him? Turkey has threatened to deport many of the prisoners in Kurdish-run northern Syrian camps, claimed after Turkey’s recent invasion. When the mothers return to a Europe that has no choice but to accept them, what happens to the children then?

Complicating matters are questions about whether the detainees – mothers, fathers, and children – would be better repatriated under controlled circumstances, rather than risk having them break free from the camps, which are currently under-manned and under-resourced, the more so since the Turkish invasion, which caused many of the Kurds to flee.

Yet even under controlled, monitored returns, most Europeans acknowledge that any prison sentences the detainees would face would be brief. Indeed, in Switzerland and some Scandinavian countries, some ISIS returnees have faced no detention at all. The children, despite having been schooled in jihad from the age of 8 or 9, would be the least likely to be sent to prison, and more likely placed in the custody of relatives. And there is no knowing what the religious and political ideologies of those relatives may be.

Then there is the problem of Islamic schools in the Netherlands and elsewhere in Europe, many of which have Salafist, extremist leanings. In September, the Dutch intelligence agency AIVD (Algemene Inlichting en Veiligheids Dienst) warned that Salafists are intensifying their grip on these schools, where children learn that non-Muslims deserve the death penalty, and that it’s better to congratulate someone for murder than to wish them a “happy Christmas.” According to Dutch national newspaper, NRC Handelsblad, which engaged in its own investigations, the lesson books for these schools include explanations about the evil of polytheism. Praying to anyone other than Allah is “a form of rebellion against Allah,” says one book. And anyone who rebels, is considered an “enemy” of Islam.

“‘What does Allah do with the enemies of Islam?'” the NRC quotes the book as asking. The answer, the article says, “can be found a page earlier, in a story about two enemies of Islam. Allah has promised to punish them in a Fire of flames.”

This is all bad enough. But imagine what happens when you send children already indoctrinated in anti-Western ideology, children who learn to count by watching public lashings, children who, before they have all their adult teeth, are threatening to “slaughter” non-Muslims and have already practiced the dubious art of beheading, to such a school – not in Syria or Iraq – but in the secular, Judeo-Christian and free democracies of Europe.

On the other hand, these children are also traumatized, says Nikki Sterkenburg, a Dutch journalist and extremism and counter extremism adviser to Europe’s Radicalization Awareness Network, among others. “Not repatriating them means exposing them to more trauma. We’ve seen reports on the situation in camps where children are confronted with hunger, freezing temperatures, abuse, other children dying, a lack of water, etc.” she wrote in a recent e-mail.

And although taking them from their mothers is in itself traumatic, she points out, “separating them from their mothers will happen anyway if the children are being repatriated with their mothers, because their mothers will be detained in the Netherlands and prosecuted.” This, however, is still not the same as being brought to another country, with little chance of seeing their mothers again.

Moreover, most of the Dutch children in question are under 6 years old – too young to have received jihadist training, though they may have been indoctrinated by their parents. Arguably, then, by rescuing the children from the horrific conditions of the camps, Dutch officials will be seen in a better light, the heroic “good guys” in the battle who have brought them to a better life (warm clothes! Enough food! Videogames! TV!).

And in part because they are so young, Sterkenburg is optimistic about these children’s chances for deradicalization, despite a generally dismal success record among deradicalization programs overall. At the June Society for Terrorism Conference in Oslo, she says, Kristian Warpinski. a Ph.D. candidate at Georgia State University focusing on foreign fighting and youth radicalization, noted that “children easily adapt to the role of tiny fighters, but at the same time, they easily adapt back.” The success of rehabilitation programs with child soldiers from Sierra Leone and elsewhere suggests that similar results may be possible here.

But others are less confident, and so, less inclined to take a chance – particularly if the Kurds insist on sending children only with their mothers, which they have indicated they will do. “Repatriating these women means rewarding them for all the irresponsible behavior they’ve shown all these years,” Belgian women’s rights activist Darya Safai told Dutch news site Nu.nl. “They’ve fought against human rights and all our values.”

Those in Safai’s corner prefer the children and their mothers instead be brought before tribunals in Iraq. “It is not our responsibility to fetch these women,” she told Nu. And while she has sympathy for the children, she would prefer only to repatriate orphans “because their mothers won’t come after them. It is important we protect our community.”

But to do that, discussions need to move further than they have to date. Europe has dragged its feet in handling the inevitability of this problem. As Sterkenburg noted, “At least this decision is forcing a debate about this … I think this court ruling has raised some awareness that you cannot deny this issue. And because the court case took place in the same weeks as the Turkish intervention, this even strengthened the awareness of the matter.”

But with awareness comes few answers, and no solutions – just the growing recognition that not only the danger, but the tragedy, of the Islamic State continues.

Abigail R. Esman, the author, most recently, of Radical State: How Jihad Is Winning Over Democracy in the West (Praeger, 2010), is a freelance writer based in New York and the Netherlands. Her next book, on domestic abuse and terrorism, will be published by Potomac Books. Follow her at @radicalstates.

The Investigative Project on Terrorism kindly allows Modern Tokyo Times to publish their articles. This important think tank provides essential information in the area of terrorism.

https://twitter.com/TheIPT Investigative Project on Terrorism twitter account

http://www.investigativeproject.org/ – Investigative Project on Terrorism

https://www.investigativeproject.org/8187/dutch-court-case-reignites-europe-focus-on-isis